It seems like almost every day now we see in the news and read in newspapers about the increasing pressures on our NHS, strains on resources and the daily challenges facing already overworked GP staff.

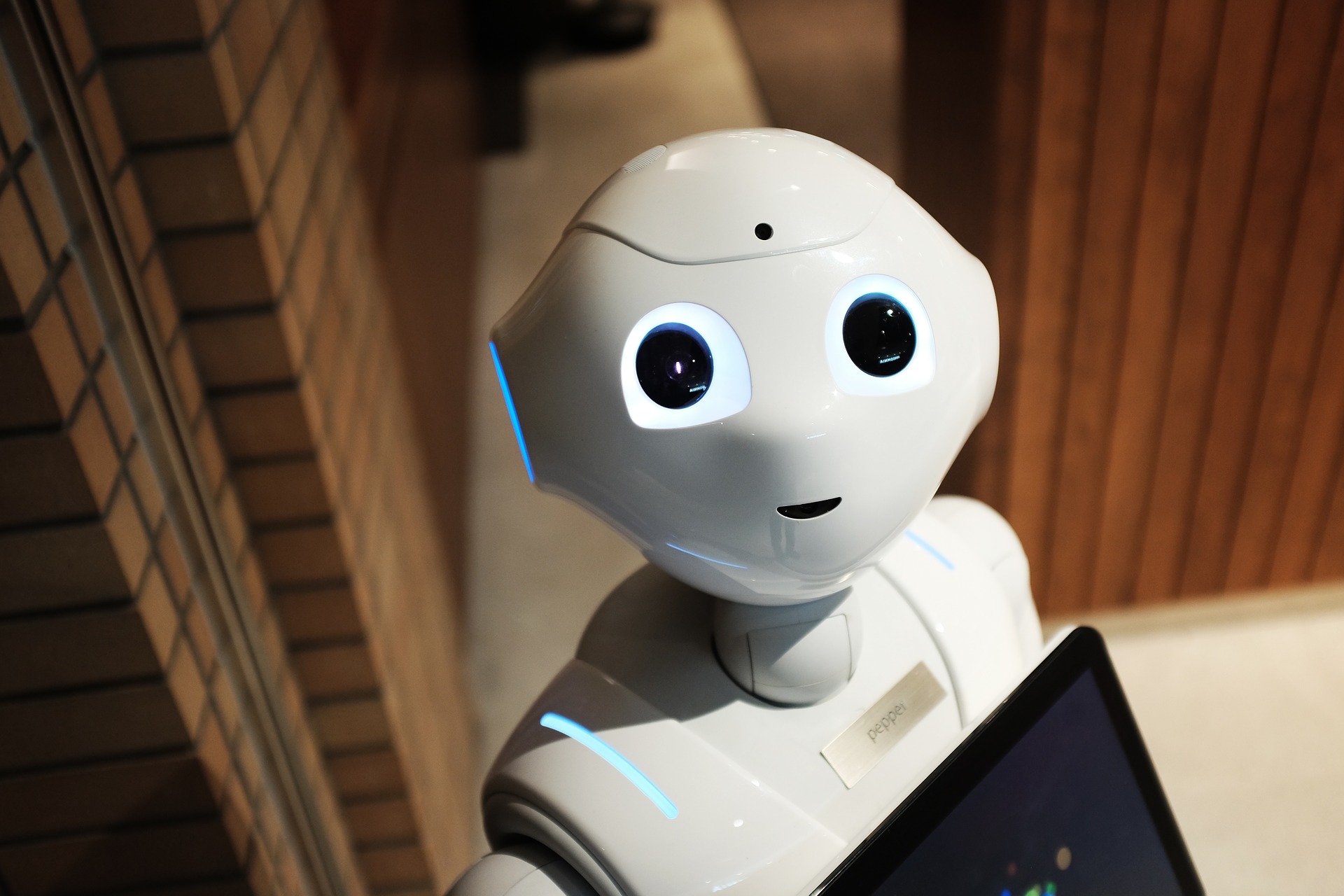

Mobile health applications (m-health apps) are increasingly being integrated into practice and are now being used to perform some tasks which would have traditionally been performed by general practitioners (GPs), such as those involved in promoting health, preventing disease, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and signposting to other health and support services.

How m-health is transforming patient interactions with the NHS

In 2015 International Longevity Centre research found some distinct demographic divides on health information seeking behaviour. While 50% of those aged 25-34 preferred to receive health information online, only 15% of those aged 65 and over preferred the internet. The internet remained the favourite source of health information for all age groups younger than 55. And while not specifically referring to apps, the fact that many people in this research expressed a preference to seek health information online indicates that there is potential for wider use of effective, and NHS approved health apps.

A report published in 2019 by Reform highlighted the unique opportunity that m-health offered in the treatment and management of mental health conditions. The report found that in the short to medium-term, much of the potential of apps and m-health lies in relieving the pressure on frontline mental health services by giving practitioners more time to spend on direct patient care and providing new ways to deliver low-intensity, ongoing support. In the long-term, the report suggests, data-driven technologies could lead to more preventative and precise care by allowing for new types of data-collection and analysis to enhance understandings of mental health.

M-health, e-health and telecare are also potentially important tools in the delivery of rural care, particularly to those who are elderly or who live in remote parts of the UK. This enables them to submit relevant readings to a GP or hospital consultant without having to travel to see them in person and allowing them to receive updates, information and advice on their condition without having to travel to consult a doctor or nurse face-to-face. However, some have highlighted that this removal of personal contact could leave some patients feeling isolated, unable to ask questions and impact on the likelihood of carrying out treatment, particularly among older people, if they feel it has been prescribed by a “machine” and not a doctor.

Supporting people to take ownership of their own health

Research has suggested that wearable technologies, not just m-health apps, but across-the-board, including devices like “fitbits”, are acting as incentives to help people self-regulate and promote healthier activities such as more walking or drinking more water. One study found that different tracking and monitoring tools that collect and analyse health and wellness data over time can inform consumers of their baseline activity level, encourage personal engagement in health and wellbeing, and ultimately lead to positive behavioural change. Another report from the International Longevity Centre also highlights the potential impact of apps on preventative healthcare; promoting behaviour change and encouraging people to make healthier choices such as stopping smoking or reducing alcohol intake.

Home testing kits for conditions such as bowel cancer and remote sensors to monitor blood sugar levels in type 1 diabetics are also becoming more commonplace as methods to help people take control of monitoring their own health. Roll-outs of blood pressure and heart rhythm monitors enable doctors to see results through an integrated tablet, monitor a patient’s condition remotely, make suggestions on changes to medication or pass comments on to patients directly through an email or integrated chat system, without the patient having to attend a clinic in person.

Individual test kits from private sector firms, including “Monitor My Health” are now also increasingly available for people to purchase. People purchase and complete the kits, which usually include instructions on home blood testing for conditions like diabetes, high cholesterol and vitamin D deficiency. The collected samples are then returned via post, analysed in a laboratory and the results communicated to the patient via an app, with no information about the test stored on their personal medical records. While the app results will recommend if a trip to see a GP is necessary, there is no obligation on the part of the company involved or the patient to act on the results if they choose not to. The kits are aimed at “time-poor” people over the age of 16, who want to “take control of their own healthcare”, according to the kit’s creator, but some have suggested that instead of improving the patient journey by making testing more convenient, lack of regulation could dilute the quality of testing Removing the “human element”, they warn, particularly from initial diagnosis consultations, could lead to errors.

But what about privacy?

Patient-driven healthcare which is supported and facilitated by the use of e-health technologies and m-health apps is designed to support an increased level of information flow, transparency, customisation, collaboration and patient choice and responsibility-taking, as well as quantitative, predictive and preventive aspects for each user. However, it’s not all positive, and concerns are already being raised about the collection and storage of data, its use and the security of potentially very sensitive personal data.

Data theft or loss is one of the major security concerns when it comes to using m-health apps. However, another challenge is the unwitting sharing of data by users, which – despite GDPR requirements – can happen when people accept terms and conditions or cookie notices without fully reading or understanding the consequences for their data. Some apps, for example, collect and anonymise data to feed into further research or analytics about the use of the app or sell it on to third parties for use in advertising.

Final thoughts

The integration of mobile technologies and the internet into medical diagnosis and treatment has significant potential to improve the delivery of health and care across the UK, easing pressure on frontline staff and services and providing more efficient care, particularly for those people who are living with long-term conditions which require monitoring and management.

However, clinicians and researchers have been quick to emphasise that while there are significant benefits to both the doctor and the patient, care must be taken to ensure that the integrity and trust within the doctor-patient relationship is maintained, and that people are not forced into m-health approaches without feeling supported to use the technology properly and manage their conditions effectively. If training, support and confidence of users in the apps is not there, there is the potential for the roll-out of apps to have the opposite effect, and lead to more staff answering questions on using the technology than providing frontline care.

Follow us on Twitter to see which topics are interesting our Research Officers this week.

If you enjoyed this article you may also like to read:

You must be logged in to post a comment.