During a recent visit to Berlin, I took the train from Zoologischer Garten station for the short journey to Potsdam. This former East German city is best known for a conference that shaped the future of post-war Europe. It’s now part of the tourist trail for visitors looking to explore the palaces, parks and gardens that were once the playgrounds of Prussia’s royal family.

My purpose in visiting Potsdam was to seek out an exhibition about a more modest type of residence. Since September, Das Minsk gallery has been exploring how East Germany’s prefabricated concrete housing is represented in art.

The plattenbau model

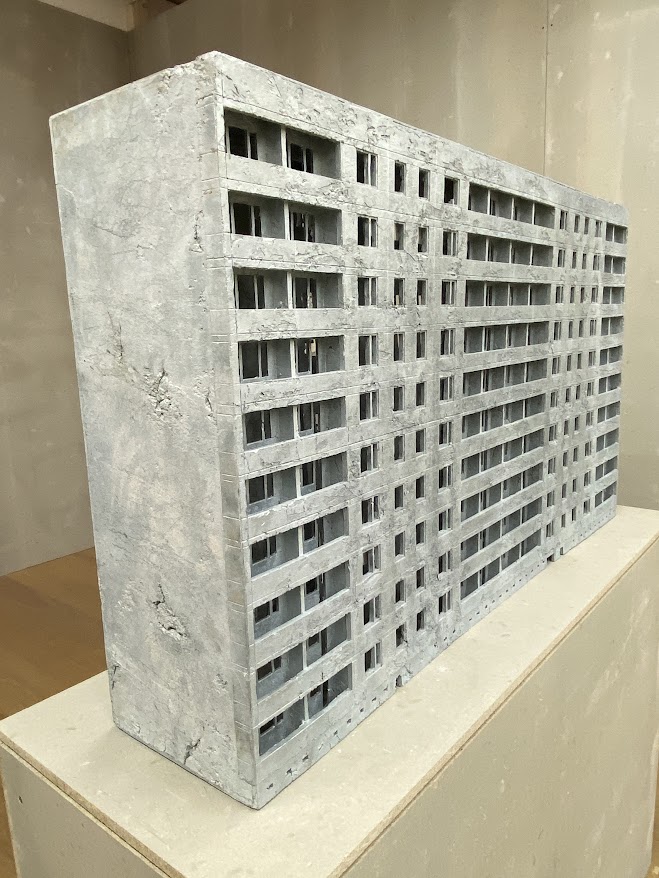

The exhibition features work by around fifty artists, who use paintings, drawings, photography, film and sculpture to consider the cultural legacy of the so-called plattenbau (slab-building) model of housing construction.

The plattenbau model grew out of necessity. After the Second World War, Berlin was divided into sectors by the victorious Allied Powers. The Soviet sector later became capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), a socialist state in the orbit of the Soviet Union. With so much of Berlin in ruins, the need for new housing was essential. Starting in the 1950s and accelerating in the 1970s, prefabricated concrete blocks of housing were quickly built across the country.

In East Berlin, this building boom reached its peak in 1977, with the construction of a vast housing estate in the Marzahn district, north-east of the city centre. Some sources have estimated that over 3 million people were housed in Marzahn.

The exhibition offers reminders that this type of housing led to a ‘collective memory’ for many of their residents. So standardised were the layouts that neighbours could easily find their way around any plattenbau apartment. “East Germans joked about never having to ask where the toilet was if they visited a stranger’s home,” Kito Nedo, the curator of the exhibition told The Guardian.

Although the large blocks of uniform housing appear stern and forbidding, they were a godsend to East Germans who had been living in run-down accommodation. The new flats had indoor toilets and district heating alongside good amenities such as public transport, schools, shops and community centres. Their success is a reminder that although freedoms and consumer goods taken for granted in the West were not available in East Germany, the country was more progressive in some areas than its Western neighbours.

A difficult transition, from communism to capitalism

In her book, Beyond The Wall, Katja Hoyer describes a country where unemployment was virtually non-existent, free childcare meant more women could enter the workforce much sooner than their Western counterparts, and there was a genuine sense of pride among many East Germans in the country that emerged from the ashes of war.

Of course, the darker side of life in the GDR became clear after the reunification of Germany in 1990. It turned out that residents who were considered to be comrades and friends were also monitoring and reporting on their neighbours as part of a massive state surveillance operation, with the intention of preventing and suppressing any opposition to the communist regime.

After German reunification, estates like Marzahn went into decline. Some buildings were demolished, others were renovated, but many were neglected. Rents began to rise, factories closed and unemployment grew. Resentment at being left behind while other parts of Germany flourished caused growing numbers of young people to find ways of finding escapism and expressing their anger.

The Potsdam exhibition doesn’t shy away from this period. An installation by Henrike Naumann recreates two corners of rooms from plattenbau apartments and depicts different subcultures of the early 1990s. One of these shows a video with a group of ravers getting high on drugs, while the other features neo-Nazi paraphernalia.

Lessons from the past?

As well as considering the past, the exhibition also raises issues that are important for our own times. As Kit Nedo explained: “The biggest question in the room, more relevant than ever in Germany and cities across Europe, is how to create affordable, quality housing. The housing plan of the GDR was an historic attempt to address this question. It’s one politicians are called on to find an answer to today.”

As in Germany, here in the UK prefabricated building played an important role in re-housing populations made homeless by war damage or living in sub-standard conditions. Today, prefab construction is making a comeback, this time re-branded as ‘modular construction.’ Using high quality, hardwearing materials, built by skilled workers and coming in a variety of designs, some of these factory-assembled homes can be built in as little as a week. This fast turnaround is a significant plus point for governments hurrying to address national housing shortages.

Final thoughts

The artworks in the Potsdam exhibition demonstrate that our impressions of prefabricated construction may need to be reappraised. At the same time, they are not an attempt to whitewash the darker side of life in the plattenbau estates. “It’s not about celebrating ‘Ostalgie’ — the nostalgia of the former East Germany — curator Kit Nedo told DW. Instead, the exhibition is intended to draw attention to neighbourhoods that have been neglected and forgotten, “and perhaps as a call to deal with them.”

Wohnkomplex: Art and Life in Plattenbau is on show at Das Minsk gallery, Potsdam, until 8 February 2026.

Share

Related Posts

“Artists have embraced the street and the built environment as integral to their work and practice, individual pieces reflecting context and location as surfaces become living canvases, rehumanizing the urban landscape.” – Asli Aktu: Shaping Places Through Art “In the ....

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has estimated that over 1 billion people are living with some form of disability worldwide – that’s about 15% of the world’s total population. And, with trends in life expectancy and the prevalence of chronic ....

From everyone at The Knowledge Exchange and our parent company Idox, we’d like to wish you a very Happy Christmas, and all good wishes for 2022. The enquiries service of The Knowledge Exchange will close on 24 December, and reopen ....

If 2020 was the year of the coronavirus, then 2021 was surely the year of the ‘coronacoaster’. From the highs of vaccine rollouts and loosening of social restrictions to the lows of fluctuating case numbers and a worrying new virus ....