Crowdfunding image via Rocio Lara (CC BY-SA 2.0)

By Morwen Johnson

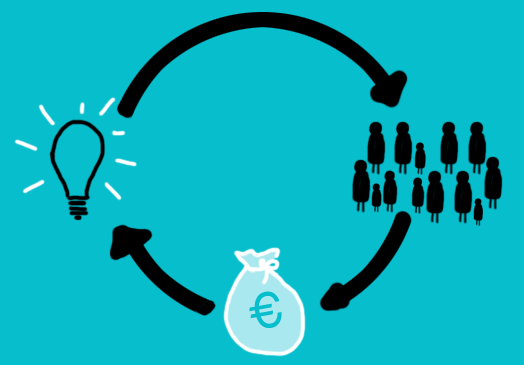

Finding money to fund community-led regeneration projects has always been difficult and as public budgets continue to be stretched, it can be hard to balance and prioritise the needs of different communities and groups. We’ve written on this blog before about how digital platforms are providing new ways to engage the public in government decision-making. So we were interested to hear that crowdfunding is also being explored for its potential to improve financing of regeneration.

Civic crowdfunding initiatives exist in Europe (for example, Voor je Buurt in the Netherlands, and Goteo in Spain) but they don’t explicitly involve public bodies as part of the crowd. But now the Mayor of London and Greater London Authority (GLA) is piloting an innovative way to plan and fund projects which puts local communities at the centre of the process. Working in partnership with the crowdfunding website Spacehive, the GLA is using a platform to enable local organisations to propose ideas for civic projects or new uses for unused space.

How it works

The Mayor pledges up to £20,000 to support the best proposals, with money coming from the High Street Fund. Public funds can make up no more than 75% of total project costs. Local organisations have to raise match funding from the wider community in order to unlock these public funds and make their projects a reality.

So far, the progress of the Crowdfunding Programme has been good. The first round received 81 proposals, 17 of which were supported, raising 118% match funding from the crowd. And in the second round, the GLA pledged £285,000 to 20 projects, leveraging over £450,000 of additional pledges – a 158% increase in funding. The third round of the programme is currently underway.

The programme was recognised as one of eleven leading examples of government innovation at the World Government Summit in 2016.

Putting local communities in the driving seat

A recent event held as part of the London Festival of Architecture looked at the early experiences of the programme and asked what the implications are for digital citizenship and community participation. Speakers from the GLA, Centre for London, Spacehive, Arup and one of the funded projects (Peckham Coal Line) debated whether it offers a practical solution to the need for a bottom-up, place-based approach to regeneration.

The event raised a lot of questions for anyone interested in strategic planning, public engagement and citizenship, reflecting the fact that this is a new approach.

- Should publicly-driven campaigns be allowed to dictate urban change?

- Is it simply rewarding communities who already have motivated and engaged residents, rather than areas which need capacity building?

- Do organisations such as local authorities have the skills or political will to behave in the agile and nimble way that such platforms require?

- To what extent is long-term sustainability or maintenance issues addressed if funding is used to kick-start community projects? Are projects an end in themselves or is the aim to help the public sector see the value in an initiative in order to adopt it and fund it themselves?

- What is the potential for scalability or replicability in funding very local projects?

- And finally, there is the fundamental question of what role should crowdfunded community projects be playing in the grand scheme of regeneration? Do they have to be making a serious contribution to improving outcomes or can they be fun and frivolous?

Early lessons

A key message was the importance of offline activity. A project is unlikely to succeed in generating match-funding if it’s unable to mobilise the local community and businesses behind the idea. The speakers also highlighted the importance of managing expectations. In some cases the projects being funded are just testing the feasibility of a concept. People making pledges need to realise this in order to prevent the cynicism that could result from perceived non-delivery.

From the point of view of creating engaged citizens, initiatives such as this can help the public understand the hard choices that need to be made, in a similar way to participatory budgeting exercises. The platform also has the potential to evolve, for example if there are buildings available for pop-up or temporary use, then a similar process could advertise and select projects to occupy them.

Civic crowdfunding as a route to creating and enabling change

Generally, local government processes are oriented around handling and dealing with complaints, rather than positive interactions and generating ideas and change. So it was refreshing to hear about a public body trying to turn this on its head.

And it seemed that – done well – civic crowdfunding is not a substitute for the role of local government in enabling regeneration. In fact, it increases the need for someone to be interpreting these local ideas into a wider, long-term vision for place.

Enjoy this article? Read these other articles written by our team:

- The Hackable City: a new dialogue with citizens

- Top 5 crowdsourcing initiatives in government: better engagement with citizens

- The digital world … why local government is stil running to catch up

- Smart citizens, smarter state: from open government to smarter governance

- Going green together: regeneration through shared spaces

- Street art: regeneration tool or environmental nuisance

Follow us on Twitter to see what developments in policy and practice are interesting our research team.

Share

Related Posts

Tackling geographical inequalities is critical for ensuring that all parts of the country have the potential to prosper. When the UK was a member of the European Union, it was entitled to a share of funding from the EU’s structural ....

By Ian Babelon A new-old concept for proximity “Are we there yet?” Parents may patiently nod to their children’s insistent nudges on a 20-minute journey to… somewhere. Quite rightly, researchers have asked: twenty minutes to what? The answer may well ....

Following the adoption of National Planning Framework 4 (NPF4) at the end of February, the Scottish planning system and planning services are dealing with transitioning to a development plan system without statutory supplementary guidance and where the relationship to current ....