Back in December, I attended the International Symposium on Evaluating Digital Cultural Resources at the newly refurbished Kelvin Hall in Glasgow.

Back in December, I attended the International Symposium on Evaluating Digital Cultural Resources at the newly refurbished Kelvin Hall in Glasgow.

The day provided an opportunity for researchers and professionals with an interest in culture and heritage in Scotland to come together to consider how digital technologies are transforming the sector. Key questions addressed included what digital culture means in practice, and how to demonstrate the benefits for both professionals and the public who experience culture and heritage in galleries, libraries, museums and other cultural spaces.

Whose ‘culture’ is it anyway?

A number of the studies presented during the day argued that making a collection ‘digital’ does not necessarily make it accessible. In some instances “preserving” collections by digitising them can actually make sources less accessible to members of the general public than if they had been kept in “hard copy” – raising the question of who exactly the material is being preserved for.

Is it for the benefit of researchers and archivists of the future? Or is the aim to present heritage and culture in a new way, preserving it, but in a way which makes it more engaging to the general public?

Questions were raised about public access, digital copyright, online availability, online cataloguing and digital databases – sometimes collections can remain as hidden as they had been before they were digitised, due to paywalls or complicated and over-elaborate online archives.

And it was clear throughout the day that delegates and speakers were wrestling with the notion of “ownership of digital cultural resources”. One example highlighted was that of Scotland’s Sounds, an audio archive of recordings which is held in the National Library of Scotland. These are resources captured in communities, donated by people and groups who want their local heritage to be preserved.

However, when it is held in a collection within a national institution, decisions about these resources are centralised with curators. They decide which elements of the collection should be exhibited and when. And they design the layout of the collection and the edited versions of recordings. Is the power of creation taken away from the original creators in this process? And does “going digital” actually make the resources, while preserving them, more inaccessible to local people who could be daunted by the prospect of visiting a national institution or may not be able to travel.

Researchers from the online archive database project ENUMERATE found that only 3-4% of digitised cultural heritage collections are available through Wikipedia (which is the world’s 7th most viewed website). What is the point, they asked, of investing in digitising if collections are as inaccessible as they were before?

This also ties in with the question of who the intended audience is. Publicly funded museums and galleries are increasingly asked about their “audience reach”. Digitising colections and making resources findable by anyone in the world may increase website visits and page hits but does this have the same value as engaging with targeted or local communities? It depends on the mission of the heritage organisation and what they view success to be.

Justifying spend and showing value

Project managers at the conference reported that they were facing a constant struggle to fund online developments. And in many cases, in the period of time from commissioning to implementation the technology and expectations moves on again.

Demonstrating value and impact are central to securing and reporting on how funds are spent in relation to digital collection projects. Funding bodies like the Heritage Lottery Fund have a set of deliverable requirements which should be included in funding bids in order to exemplify good and sustainable use of funding, particularly in relation to digital projects. This includes creating resources which have a long life span (the favoured format is online PDF uploads, although they are trying inhouse to diversify their content); creating projects that will preserve heritage and benefit communities; and creating projects which have ambition and are easy to use, while also contributing to the organisation’s wider digital infrastructure and outcomes plan (which may also include interactive exhibitions and the provision of public Wi-Fi).

A unique opportunity to bring history and culture to life for new learners

When bidding for funding, cultural heritage organisations will often claim the project will support learning within their communities. However, many write this in their “digital strategy” without really knowing what it could or should mean in practice. How schools and other learners can engage with digital cultural projects is important not only to showing their value but to developing the collections in the future, making them representative or the interests and desires of their local communities.

Technology-enhanced learning was something which many delegates raised as one of the major potential benefits of digitising collections. In addition to the benefits for planners (particularly erosion and building management specialists) and the tourism industry (through virtual reality city tours which show what an area looked like hundreds of years ago) delegates stressed that one of the primary aims of digital collections was to make it easier for material to be used as a tool for learning. An example given at the conference was the REVISIT project which was run in Glasgow and focused on the British Empire Exhibition of 1938 which took place in Bellahouston Park in Glasgow. The project created a 3D visualisation of over 100 buildings from the exhibition. The modellers worked from dozens of small-scale drawings, hundreds of photographs and many maps to recreate the 3D virtual Empire Exhibition as well as mapping roads, pathways and other transport systems in the area. These were then uploaded to an online repository, with accompanying text, where they could be viewed and “explored” using navigation tools.

The aim of the project was to create a permanent resource for the exploration, research and public exhibition of the Empire Exhibition of 1938 in the context of Scottish and UK social and architectural history. Researchers used a variety of archived material, newspaper articles, photos and interviews with people who attended the exhibition to create the interactive map. They then invited local school children to use the resources to inform their learning on the topic through a series of guided workshop sessions and interactive group activities. The 3D maps were a learning resource but also a tool to generate discussion and questioning about the period and the exhibition itself.

Measuring the “impact of digital” in cultural spaces

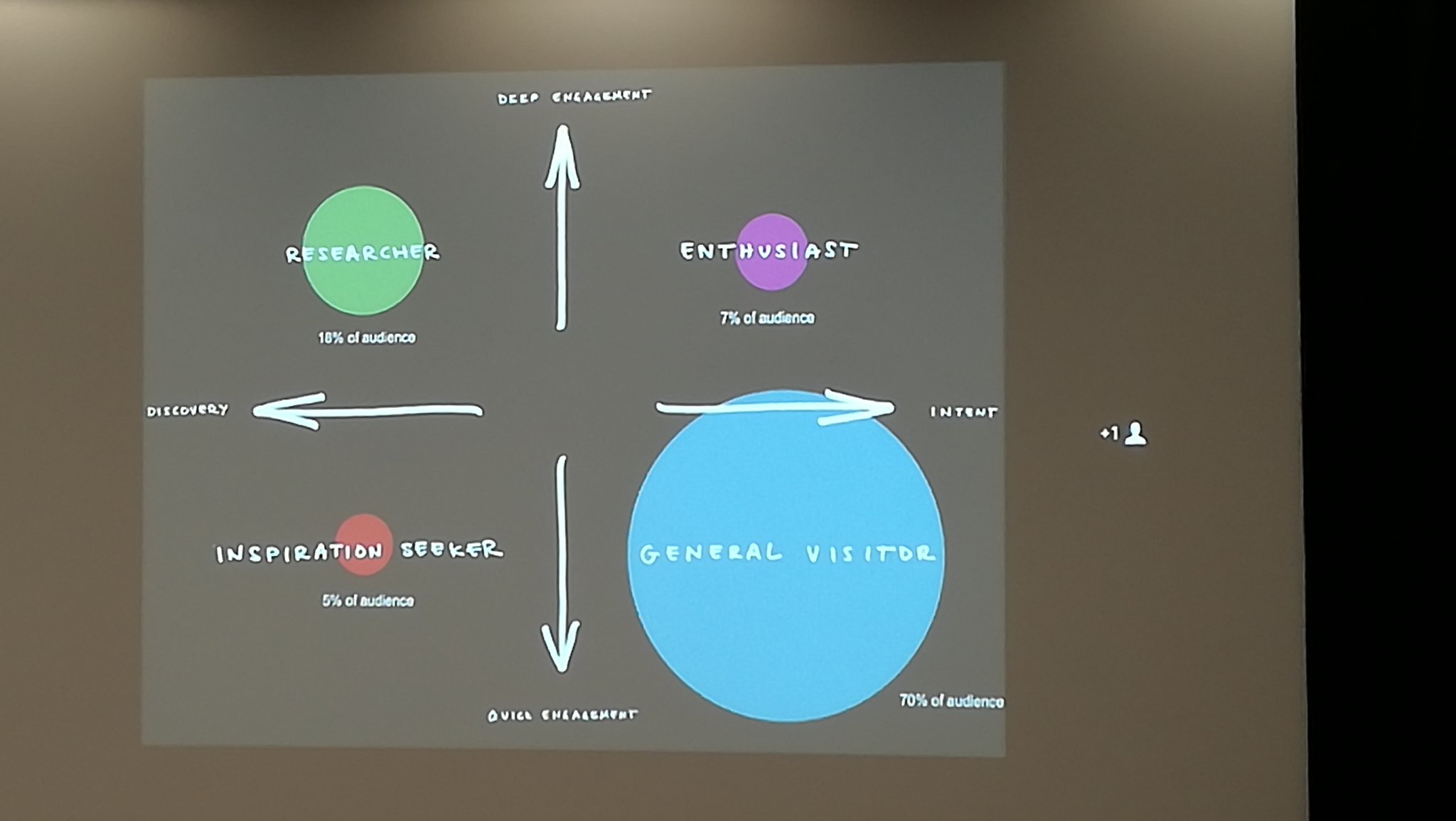

One of the most interesting sessions of the day involved input from the V&A in London. It highlighted how mapping and analytics, as well as a more functional understanding of users and visitors to the museum, can be used to help during digital planning. The way that consumer research around digital cultural resources is done can help refine digital programmes in an efficient and cost effective way.

Kati Price from the V&A led a discussion on the creation of new digital platforms and how important understanding user preference can be in design and functionality of digital resources in a museum setting. She highlighted their use of agile methods to test the usability and effectiveness of some of the new digital content produced by the V&A, including new audio guides. In terms of measuring outcomes in digital strategies, she stressed the importance of being flexible with your evaluation methods but also to consider what are you measuring, when in the process are you measuring it, and why and to what end are you measuring it.

Summing up

The day provided useful insight into the challenges and opportunities of digital for cultural and heritage organisations.

It highlighted the adaptability of cultural spaces to digital environments, and the value and benefit to collections of “going digital”. It also identified some potential directions for the future, such as 3D printing to create replicas and Virtual Reality platforms to create more immersive and interactive learning spaces.

It is clear, however, that if the cultural heritage sector is to make the most of what could potentially be game-changing technology, museums, libraries and other organisations need to work closely with communities to make sure they remain connected to their heritage and do not get left behind by this digital revolution.

Cultural spaces need to be mindful of potential exclusion and work to promote digital engagement, skills and education to allow people to access and contribute to the future growth of digital collections in Scotland and the UK.

Reading Room (an Idox company) is one of the UK’s leading digital agencies and has extensive experience working with museums and libraries on award-winning digital projects. Clients include the British Library, Arts Council England, The National Archives, and Durham Council (Durham at War archive). If you’d like to talk to us about how we can help your organisation with developing your digital strategy, contact info.uk@readingroom.com

Share

Related Posts

Supporting residents on the decarbonisation journey: leveraging data for effective retrofit projects

As the drive towards decarbonisation intensifies, the social housing sector’s ability to collect, store and manage vast amounts of data becomes increasingly critical. With a shared goal of creating warmer, carbon-free homes, housing associations’ strategic use of data is essential ....

By Hannah Brunton UNESCO’s Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2022 takes place from 24-31 October 2022 under the theme of “Nurturing Trust”, giving governments, educators, information professionals, and media professionals the chance to discuss and reflect on critical issues ....

“Artists have embraced the street and the built environment as integral to their work and practice, individual pieces reflecting context and location as surfaces become living canvases, rehumanizing the urban landscape.” – Asli Aktu: Shaping Places Through Art “In the ....