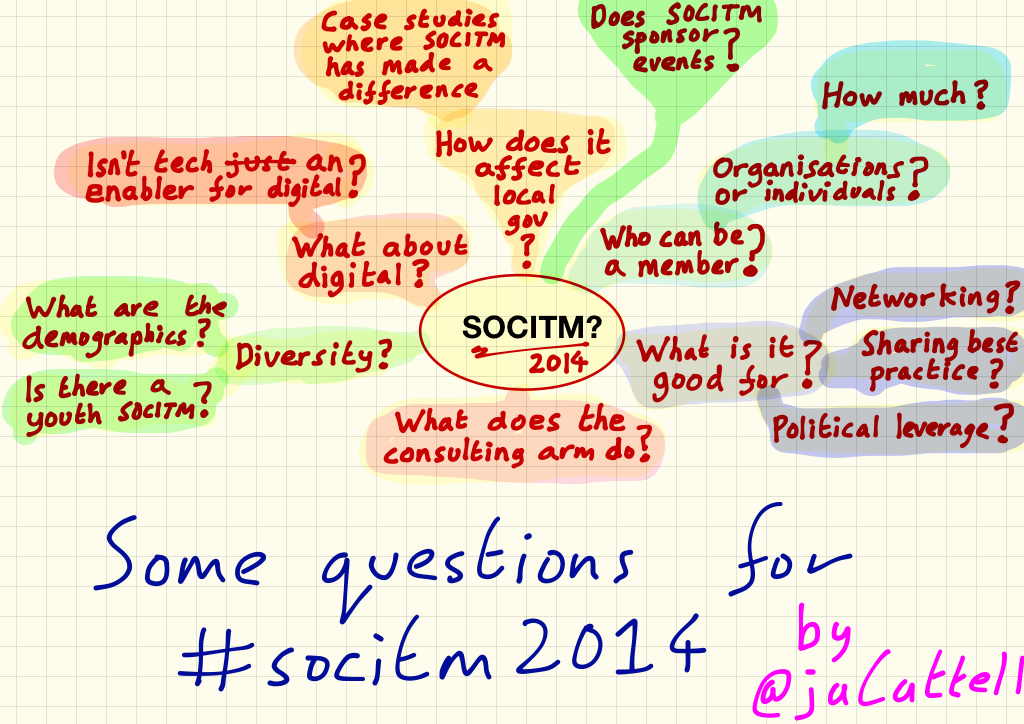

Image by James Arthur Cattell via Creative Commons

By Steven McGinty

On April 21st, Socitm (the Society of Information Technology Management) will be having their annual spring conference. This year, the agenda reflects the challenges facing technology leaders, who are under increasing pressure to radically transform services and deliver financial savings.

The event will open with a discussion on how digital technology should be used to provide the public services of the future. In anticipation of this, I thought I’d highlight some of the issues that may be discussed.

Open architecture and platforms

In 2012, the Government Digital Service (GDS), the body responsible for digital transformation in central government, launched GOV.UK. Within 15 months this project brought together over 300 government agency and arm’s length body websites into just one single platform. Similarly, they also introduced GOV.UK Verify, a platform rolled out across a number of departments, which allows citizens to prove who they are when using government services.

These platforms exemplify the UK Government’s new ambition for public services, i.e. that services should be simple, user-centric, and built on ‘a common core infrastructure of shared digital systems, technologies, and processes’. In theory, this should provide users with a seamless experience as they move between different government services. This approach has been referred to as ‘Government as a Platform’.

We have also seen examples of this approach adopted in local authorities. For instance, Manchester City Council’s award winning website clearly follows some of the GDS’ design principles.

Collaboration

Historically, the public sector has worked in silos, with individual departments and local authorities responsible for their own digital projects.

However, Matt Hancock, Minister for the Cabinet Office, appears keen on greater levels of collaboration, particularly with the private sector, as he believes this will lead to financial savings. For example, he highlights the joint-venture between the UK Government and Ark Data Centres to provide hosting services for the whole government. Previously, each government department would have had to agree their own bespoke contract. This joint-venture could potentially save the UK government £105 million.

Local councils have also shown a willingness to collaborate, with many joining together to sign shared information and communications technologies (ICT) service contracts with suppliers. Usually these councils are neighbours; however we’ve recently seen ‘pioneering agreements’ between councils from different regions in England. Like the hosting agreement, this collaborative approach is expected to provide better value for councils.

Data

Eddie Copeland, Director of Government Innovation at NESTA, has written widely on the need for the public sector to make better use of its data. Although this is certainly true, there have been some successful data projects, such as the London Datastore, a free and open data-sharing portal for Greater London.

Eddie Copeland has proposed that London, as well as other devolved regions, should introduce a New York style ‘Office of Analytics’. This would be led by a Chief Data Officer who would have overall responsibility for managing and coordinating data projects. He suggests that having a central office to manage data could help UK cities in a number of areas, including increasing business growth, identifying illegal housing, and predicting possible fraud.

The Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) has also announced plans to introduce a data service called GM-Connect. The service’s main purpose will be to help break down the barriers that prevent public services sharing information.

User-led approach

There is now a recognition that public services should be determined, not by the organisational and legal constraints of government departments, but by the needs of citizens. For instance, in a podcast in 2012, Mike Bracken, former head of the GDS, stated that “everything we do is based on users and user-testing.”

In the US, the city of Oakland has introduced an innovative pilot programme that assigns an ‘MVP’ (most valuable player), whose sole responsibility is to ensure that digital initiatives consider how users, outside of city hall, approach finding new services. In addition, it also uses surveys to understand how services are used, digital dashboards that display current activity on the city website, and virtual town halls, which provide an opportunity to receive direct feedback.

Multi-channel, cross platform

As technology has changed, citizens are now expecting to access public services via a range of devices, including smartphones and tablet computers. There is also the expectation that government services are able to match the experiences provided by private sector organisations such as Facebook and Google. Social media has also become so pervasive that some organisations receive more visits to their social media pages than their main websites. Public services, therefore, need to be optimised for mobility, as well as providing a consistent multi-channel service.

Conclusion

At the moment, public sector organisations are using digital technology to improve public services. However, if they are to make the savings highlighted by last year’s Spending Review, they will need to refocus their efforts on digital initiatives.

The public services of the future will need to:

- be based on a common set of shared platforms, processes and technologies

- involve a number of stakeholders working together (whether private or public sector)

- focus on the needs of users

- harness data to provide targeted interventions and optimise services

- be optimised for mobility

- provide a consistent multi-channel experience.

Follow us on Twitter to see what developments in public and social policy are interesting our research team.

Share

Related Posts

Supporting residents on the decarbonisation journey: leveraging data for effective retrofit projects

As the drive towards decarbonisation intensifies, the social housing sector’s ability to collect, store and manage vast amounts of data becomes increasingly critical. With a shared goal of creating warmer, carbon-free homes, housing associations’ strategic use of data is essential ....

By Hannah Brunton UNESCO’s Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2022 takes place from 24-31 October 2022 under the theme of “Nurturing Trust”, giving governments, educators, information professionals, and media professionals the chance to discuss and reflect on critical issues ....

In May 2020, Google-affiliated Sidewalk Labs abruptly cancelled its smart city vision for Toronto’s waterfront, citing that “unprecedented economic uncertainty” created by the pandemic had made the project unachievable. Named ‘Quayside’, the venture proposed a 12-acre development of sleek apartments ....

When we last wrote about it in 2019, Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) appeared to be on the threshold of transforming the way we get around. An innovative MaaS project had already taken off in Finland, and pilot projects in Sweden and the ....