By Rebecca Jackson

In recent years there has been a surge in the number of people in the UK being classed as ‘supercommuters’ – people who travel more than 90 minutes to work each day. And figures from the TUC published last week suggest that over 3 million of us now have long daily commutes of two hours or more, a rise of 72% in the last decade.

Rising rent, the London-centric nature of the British economy and the desire to maintain a healthy work-life balance have all been cited as factors which have contributed to this mass commute which millions of us, myself included, go through every day.

Reliance on commuting for ‘better job’ opportunities

In a recent survey it was found that accountants have the longest average commute, at 75 minutes, with IT software developers next at 65 minutes. The shortest average commute belongs to those who work in the retail and leisure industries, who have commute times of between 20-30 minutes respectively.

A recent IPPR report suggested that commuting, or more specifically the lack of ability to commute, was resulting in many job-seekers remaining out of work. As a result, a reliance on commuting for ‘better jobs’ was limiting the growth of the British economy, particularly in areas outside of London.

Commuting, and the resulting inflexibility this gives many jobs, can also be a barrier to many women, particularly those with families or caring responsibilities, taking on roles which are higher paid or higher up the ‘corporate ladder’, including more senior roles in company structures and professions such as accountancy and law.

The costs of supercommuting

So how realistic is a ‘supercommute’ in terms of cost, and in terms of family life and commitments … and is it worth it?

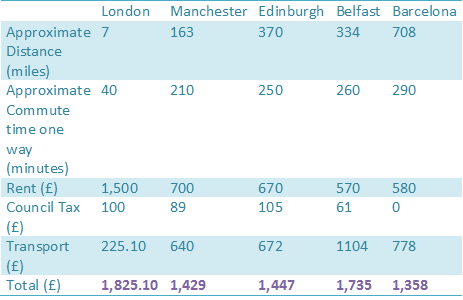

I calculated the cost and time it would take to commute to London from 4 cities: Manchester, Edinburgh, Belfast and Barcelona (I chose Barcelona because I know someone who did it for a year!).

The scenario I used was for an individual who works full time in an office in the City of London, within walking distance of Liverpool Street Station. All prices shown are averages and will fluctuate depending on proximity to amenities, time of booking transport etc. This information also does not take into account the cost of living more generally, food, utilities, socialising etc.

*Average time, without excessive traffic or delays, for flights includes check in and transfer to Liverpool Street

*Average time, without excessive traffic or delays, for flights includes check in and transfer to Liverpool Street

** Northern Irish “Rates” are slightly different to council tax

*** For a 1 month Zone 1-6 Oyster card OR to fly from MAN; EDI; BFS; BCN to STN and get the Express to Liverpool Street, 3 days per week, returning each night.

The figures seem to show that cost wise, it’s true, supercommutes can save you money if travelling means that you can take a higher wage or better job.

Work-life balance

People who supercommute, while grateful for the better lifestyle it gives them and their families on days off, often highlight how long commutes, which often mean significantly longer working days, impact on their relationships, their health and require significantly more commitment and energy from them as individuals than a ‘normal 9-5 job’ would. An individual’s personal well-being can often be hugely affected by extreme commuting times.

Statistics have also shown that people who supercommute, who have a wife or partner who doesn’t commute with them, or doesn’t undertake a similar length of commute of their own, have a higher rate of divorce and/or separation. And those with children reported stressed and difficult relationships with them too.

Studies have also shown that its not all about the money, and that to equate monetary value to distance commuted, you would need to be offered a pay rise of 40% to compensate for the detriment caused in other areas of life by an extra hour’s commute.

Another factor influencing how realistic supercommuting is as an option for employees, is the willingness of the company, and the ability of the job, to be flexible. Many people who are interviewed, or used as successful case examples of supercomputing, work in jobs where they can work remotely for part or all of the time.

And as you can see in my example above, it is based on the understanding that those commuting from outside London are only doing so on a 3 day week basis, with a view that they would work remotely from home on the other two days. Not all jobs can facilitate this, and neither can all employees.

Is it worth it?

Supercommuting can, therefore, be a way to save money, and offer improved quality of life, enabling people to live closer to family or in the countryside. However it comes at a potential cost to social life and relationships, and to personal well-being in terms of physical and mental health.

Sadly it’s not all afternoon strolls or sangria weekends on a beach in Barcelona, although this can be part of it. It takes commitment to the job and the commute itself and a regular reassessment of the question of “is it actually worth it?”

And, unfortunately for many, supercommuting is no longer a choice, but a situation forced on workers by the state of the housing or employment markets.

Follow us on Twitter to see what developments in policy and practice are interesting our research team.

Further reading: if you liked this blog post, you might also want to read Donna Gardiner’s post on remote working

Share

Related Posts

A recent item on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme generated an unusually high number of responses from listeners. A man who had lost his job in the financial services sector at the age of 57 described his difficulty in trying ....

A recent survey by the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) in July 2021 aimed to gauge UK public awareness of the planning profession. The results suggested a significant disconnect between the public perception of planning, the scope of professions in ....

It is well recognised that the UK faces a shortage in STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) skills, and that at current projections, this gap in skills and knowledge is only going to grow in the coming years. Before the ....

Yesterday marked the 111th International Women’s Day, a global day of celebration for the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women. But it is also an opportunity to reflect on and further the push towards gender equality. While there ....