by Scott Faulds

Since the early 20th century, the predominant method of evaluating the success of a country has been through the metric of Gross Domestic Production (GDP). This measurement is based upon the assumption that economic growth is the key indicator of a successful country.

In recent years, this assumption has been challenged, with politicians and economists, arguing that the focus on GDP has led to the development of policy which values economic growth at the expense of the wellbeing of society.

Following the 2018 OECD World Forum, Scotland, Iceland and New Zealand, have formed a group known as the Wellbeing Economy Governments, to share best practice of how to build an economic strategy that will foster societal wellbeing. Additionally, organisations such as the OECD, European Commission and United Nations, are all conducting research into the development of policy beyond GDP. Therefore, it is clear that the previously held consensus surrounding the use of GDP has begun to break down, with countries across the world searching for different ways to evaluate the success of policy.

“We must forge ahead with progressive economic policies that defy common stereotypes about costs and benefits and keep on promoting gender equality as part of a forward-looking social justice agenda“

Katrín Jakobsdóttir

Prime Minister of Iceland

What’s wrong with GDP?

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), GDP is the measurement of the monetary value of all final goods and services produced within a country during a given period. However, it should be noted that this measure excludes unpaid work and the economic activity of the black market. Simon Kutzents, the modern-day creator of GDP, argued that whilst GDP was effective as a measure of productivity, it should have never been used as an indicator of the welfare of a nation.

Critics of GDP contend that the measure is overly simplistic, due to its interpretation of a successful country as one which is experiencing economic growth, arguing that some countries with growing economies have many social problems. For example, in China GDP grew by 6.6% last year whilst levels of inequality rose faster than in other countries, and society faces a great deal of political oppression. Therefore, it can be said that GDP does not provide a true picture of the success of a country, as it fails to consider societal problems, such as inequality and political freedom.

The wellbeing approach

As a result of growing criticism of the use of GDP, several countries have started to look at alternative approaches of measuring success which considers factors beyond economic growth. This has led to international interest around the concept of wellbeing, a desire to create policy to improve the wellness of society.

This can manifest in a variety of different forms, from Scotland’s National Performance Framework to New Zealand’s Wellbeing Budget – both policies designed to help improve the health of society rather than solely increasing economic growth.

However, this should not be interpreted as a movement away from encouraging businesses to grow; rather the Wellbeing Economy Governments believe that by improving the wellbeing of society they will indirectly stimulate sustainable economic growth.

“We need to address the societal well-being of our nation, not just the economic well-being“

Jacinda Ardern

Prime Minister of New Zealand

As a result of creating a budget justified by improvements in societal wellbeing, New Zealand has invested record levels of funding into supporting the mental wellbeing of all citizens, with a special focus on under 24s. Additionally, the budget prioritises measures to reduce child poverty, reduce inequality for Māori and Pacific Islanders and enable a just transition to a sustainable and low-emissions economy. New Zealand believes that by tackling these inequalities, economic growth can be stimulated in ways that benefit all New Zealanders, where improvements in mental health alone could lead to an increase in GDP of 5%.

Therefore, whilst GDP isn’t the main priority of policy making under the wellbeing approach, it is possible for economic growth to occur as a result of implementing policy designed to improve the wellbeing of society. After all, according to the World Health Organisation, a healthier and happier society is a more productive society.

How well is well?

It is evident that the use of GDP as a measure of a country’s success has faced a great deal of criticism in recent years. However, some economists are not ready to give up on GDP quite yet. They argue that whilst GDP is not a perfect representation of a country’s success, neither is the wellbeing approach as it can be incredibly difficult to quantify societal wellness.

For example, if we compare one citizen who is in poor health and lives in an area experiencing low-levels of crime with another citizen who is healthy and lives in an area with high-levels of crime, how can we quantify which citizen has the better level of wellbeing?

In short, critics of the wellbeing approach argue that whilst it is vital that society’s wellbeing is considered during the policy-making process, basing policy solely around wellbeing is ineffective and would be incredibly difficult to measure, due to the personal nature of what constitutes wellbeing.

“Growth in GDP should not be pursued at any or all cost … the objective of economic policy should be collective well-being: how happy and healthy a population is, not just how wealthy a population is.”

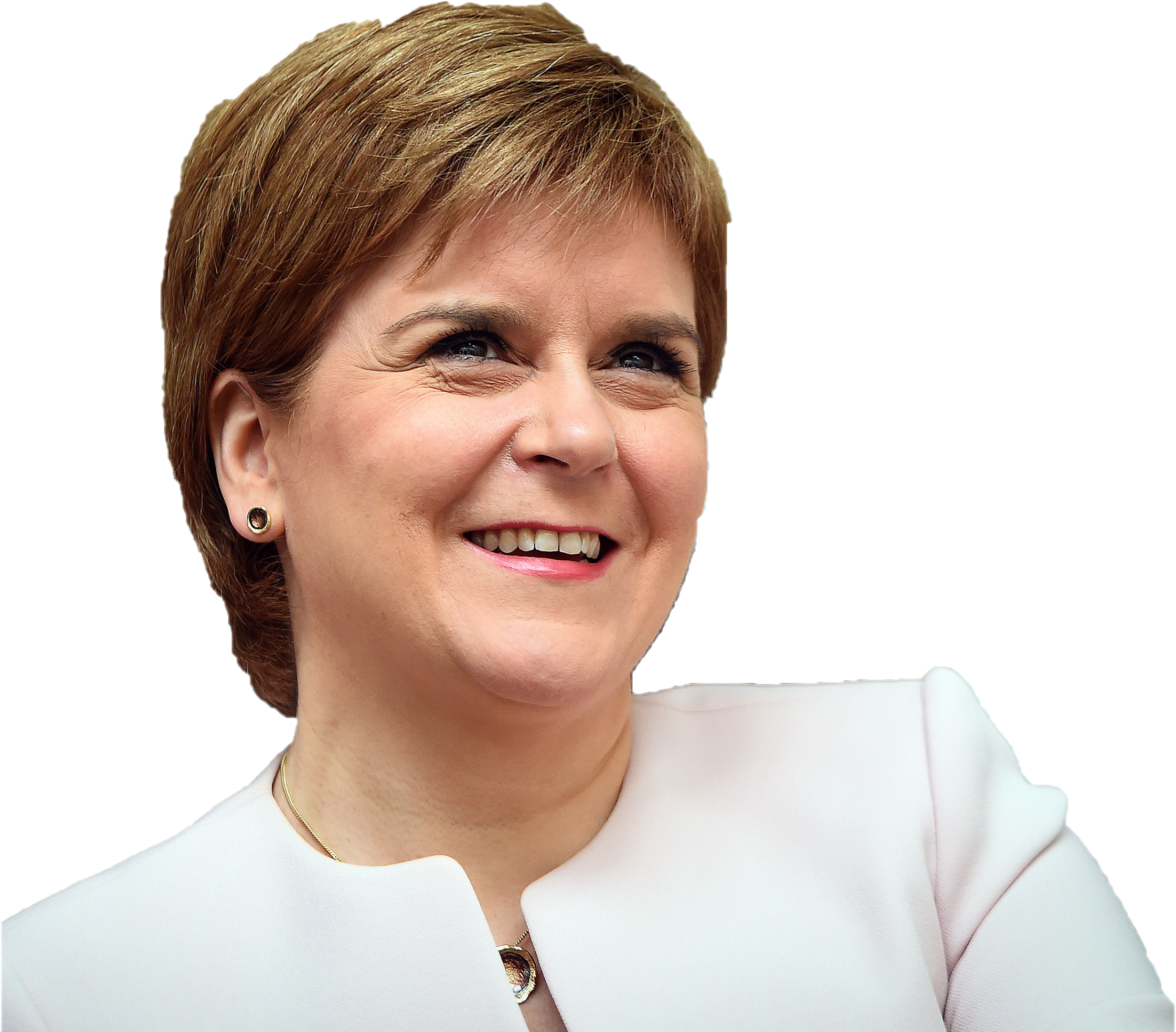

Nicola Sturgeon

First Minister of Scotland

Final Thoughts

In summary, whilst there is a great deal of international interest in the possibility of a movement away from GDP, no consensus has yet formed as to whether the wellbeing approach is the way forward. With all new forms of policy, other countries often wait to see if early adopters succeed before following their lead. Perhaps it will be left up to smaller countries to prove that an economic policy focused on wellbeing can be successful.

Until then expect to see a great deal of interest in New Zealand’s implementation of the Wellbeing Budget and the results of the second meeting of the Wellbeing Economy Governments in Iceland this autumn.

The Knowledge Exchange provides information services to local authorities, public agencies, research consultancies and commercial organisations across the UK.

Follow us on Twitter to see what developments in policy and practice are interesting our research team.

Share

Related Posts

A recent item on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme generated an unusually high number of responses from listeners. A man who had lost his job in the financial services sector at the age of 57 described his difficulty in trying ....

Tackling geographical inequalities is critical for ensuring that all parts of the country have the potential to prosper. When the UK was a member of the European Union, it was entitled to a share of funding from the EU’s structural ....

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on ensuring people with ‘lived experience’ are involved in co-producing research and policy-making at practical, local level. However, there has been little discussion around what the people with lived experience themselves ....

By Robert Kelk and Chris Drake A new start for an old challenge? The recent appointment of Marc Lemaître as the European Commission’s director general for research and innovation (R&I) has returned Europe’s R&I gap to the spotlight. Previously head ....