By Rebecca Jackson

The recent advancement of technology in society has been fast and significant. Young adults who were children themselves less than 15 years ago have admitted that, even to them, the difference in ‘childhood’ as they remember it and how it appears to be today is stark. And for many older members of the public, the advances have made ‘childhood’ almost unrecognisable. The Scottish Universities Insight Institute is currently running a series of seminars looking at digital technology across the life course, one of which considered the role of technology in relation to young children.

Common misconceptions

The debate around the use of digital technology by children is fraught with hearsay and sometimes distorted reporting of statistics in the mainstream media. This has resulted in confusion about what it means to be digitally literate, and an emphasis on the negative views that people have about children using technology.

These are some of the most common misconceptions as identified by a group of researchers from the Scottish Universities Insight Institute:

- Digital technology is just laptops and computers: When many people refer to ‘digital technology’ they talk about laptops, tablet computers and desktops. In fact, the term covers a far wider range of devices and activities. This includes cameras, video games consoles, streaming music or listening to an mp3 player or iPod, using Skype or FaceTime to communicate, mobile phones, streaming videos on youtube and watching TV or DVDs.

- Less affluent socioeconomic groups don’t have access to digital technology: While academics commented that their study showed there may not have been as many devices in lower income households, most still had access to mobile phones, televisions, the internet, a games console, an interactive toy, an mp3 player or IPod, camera or a tablet computer.

- Children engaging with digital technology comes at the expense of ‘traditional play’: Studies have shown that, contrary to popular belief, children still have more access to, and spend more time playing with, ‘traditional toys’ such as dolls, cars, soft toys and outdoor equipment. The study also highlighted that children use digital experiences to inform their own imaginative play. They were observed acting out scenes or engaging with imaginary characters from films or television programmes and pretending to use laptops and mobile phones during play, rather than using them directly.

- Children know more about digital technology than adults: Children don’t know anything until they are exposed to it – much of children’s exposure comes from parents and is representative of the use by other family members. A study also showed that if a child was completing an activity using digital technology (a video game for example) which they found too difficult or “fiddly” then this could deter them from using technology in the future.

- Children using digital technology are more socially isolated and reclusive: This is a common stereotype which is normally directed at older children and adolescents. However children of all ages have been found to use digital technology as a facilitator of social relationships. This includes the use of websites like Facebook and Twitter, as well as the use of Skype and FaceTime to communicate with overseas relatives or friends.

Blended learning

Many academics who study the impact of digitisation on children (or people in general) highlight the unhelpful nature of the “good/bad” debate. As one researcher at a recent conference held at Strathclyde University stated: “Blended learning – a combination of digital and traditional learning – is best for children and their development; quite often in studies we have found that children do this naturally themselves.”

Examples of this which were given was a child acting out a scene from the Disney film Frozen with soft toys, once they had seen the film on the television. Others could include printing out characters from films or TV shows to colour in with pencil or crayon, and children using a camera to capture memories or take photos of things which are interesting to them while outside playing or on a walk.

Same moral objections, different context

The technology may be different, but the moral questions are the same ones that have been plaguing innovations and inventions for hundreds of years. The arrival of comics, the transmission of radio (which was once thought to be toxic for children to hear), the spread of ideas promoted by television, even the electrification of homes, have all been met with some level of trepidation by the general public. Fears about digital technology and the normalisation of its use in everyday life will, academics feel, eventually be surpassed by a new technology which we can panic over instead.

Use in education

This is one of the more contentious issues for many teachers and local authorities. There are questions about the extent to which digital technologies should be integrated in to the curriculum, particularly in the early years, and the role of the teacher in relation to digital learning. It is also clear that teacher enthusiasm and training in using digital technology is important to ensure that children get the most out of digital teaching.

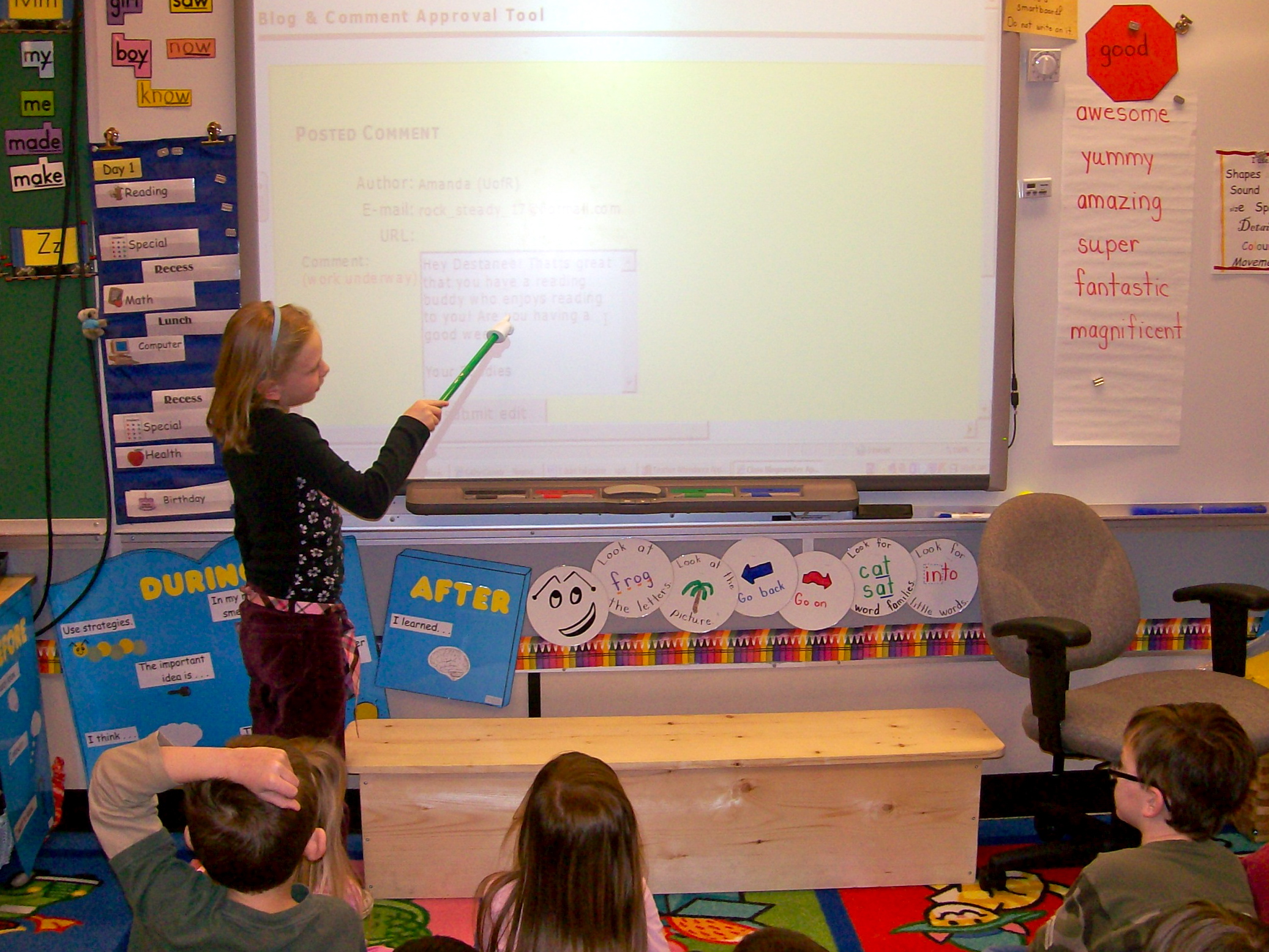

Some schools have trialled bring your own device to school initiatives, although the reception given to these has been mixed. Many schools and teachers also make use of interactive whiteboards and on-line portals to set homework and to give children access to resources. There has been a suggestion that children and teachers should work with software developers to produce more apps, programmes and effective digital learning resources.

In Scotland, integrating digital elements to the curriculum has been improved by the transition to the Curriculum for Excellence. However, some schools still struggle with a lack of resources and have to continue to make use of an “ICT slot” in order to allow children to be able to access technology on a one-to-one basis.

The general consensus among education practitioners towards digital technology appears to be positive however, with many schools using online channels to communicate with pupils and parents. Some classes have blogs which the children are encouraged to contribute to, and others have utilised online web chats to twin with schools abroad in a modern-day pen pal set up.

A right to digital literacy?

Another issue being discussed by academics and policy makers is the idea of a right to digital literacy. In the view of many, digital learning should be integrated into everyday traditional learning to equip children with digital skills. Failing to prepare children, some academics argue, would inhibit their ability to contribute effectively in a digitised world.

It is clear that the debate around digital technology and child development will continue, and there is a need for both further study and better communication of research findings to the wider public.

Read our other recent blogs on children’s policy:

- Brain food: the impact of breakfast on children’s educational attainment

- Child neglect, wellbeing and resilience – adopting an art’s based approach

- Being a young carer shouldn’t be a struggle

- The way forward for mental health services for children and young people

Follow us on Twitter to see what developments in public and social policy are interesting our research team.

Share

Related Posts

Supporting residents on the decarbonisation journey: leveraging data for effective retrofit projects

As the drive towards decarbonisation intensifies, the social housing sector’s ability to collect, store and manage vast amounts of data becomes increasingly critical. With a shared goal of creating warmer, carbon-free homes, housing associations’ strategic use of data is essential ....

A recent item on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme generated an unusually high number of responses from listeners. A man who had lost his job in the financial services sector at the age of 57 described his difficulty in trying ....

By Donna Gardiner While free school meals (FSM) have been available in England on a means-tested basis since 1944, recent years have seen a renewed focus upon the potential benefits of providing free school meals to all school-aged children. Currently, ....

By Robert Kelk and Chris Drake A new start for an old challenge? The recent appointment of Marc Lemaître as the European Commission’s director general for research and innovation (R&I) has returned Europe’s R&I gap to the spotlight. Previously head ....